During a recent study on Judaism, a question arose regarding circumcision: why did God require it? We will carefully examine Scripture to attempt to discern the answer. Before that, in continuity with our study of Judaism, we’ll do a brief overview of circumcision among Jews today.

Although circumcision is practiced across all five, major Jewish denominations, it is not uniformly observed. Reform Judaism, for instance, encourages, but does not require, circumcision of non-Jewish converts.[1] Reconstructionist Jews advocate circumcision for converts, but often are lax in enforcing that standard. Secular Jews–50% of all Israeli Jews are secular and non-practicing–have no spiritual investment with religious rites surrounding circumcision, but in many cases, decide as a cultural matter to go forward with it as a ritual event.

Rabbinical literature attaches great importance to circumcision. In the Jerusalem Talmud–considered by the Rabbis to be the “oral law” spoken by God to Moses on Mount Sinai and transmitted by word of mouth throughout the ages–circumcision is said to be so important that it is “weighed against all the mitzvot” of the Torah.[2] Of course, it might be useful to know that there are 79 other instances in which various commands, practices and precepts are considered by themselves of equal importance to 612 commandments taken together. This includes the Shabbat, wearing of Tzitzit, the pursuit of peace, tsedakah (charity), and many others.

The word “circumcision” comes from Latin, circum (meaning “around”) and cædere (meaning “to cut”). So, combined, it means to “cut around.” The Hebrew term most closely associated with the practice of circumcision among Jews is brit milah. Brit means covenant. Milah means cut.

We now turn to the Scripture to entertain the question we started with: why circumcision? If we accept that the Scripture is a portal connecting us with God, our task becomes “drawing out” the meaning of the words of Scripture that, in the end, may answer our question from God’s point of view. To that end, we have at our disposal, as independent readers of Scripture, a set of literary tools. The ones that are most visible to us in English are chiasms and parallelisms. For a more thoroughgoing description of these types of literary arrangements, please reference Identifying Literary Structures in the Scriptures.

There are a number of Scripture passages in both Testaments touching on the subject of circumcision. Often, in tracing the meaning of a Biblical practice, we are wise to reference its Scriptural origin. This study will begin with Genesis 17, the first instance in which we find circumcision. The key verses in which God establishes the covenant of circumcision with the patriarch Abraham are 17:9-14. However, to capture the “context” of this covenant, let’s “widen” our reading, beginning with verse 17:3 and ending with the first line of verse 17.

3 Abram fell on his face, and God talked with him, saying,

4 “As for Me, behold, My covenant is with you,

And you will be the father of a multitude of nations.

5 “No longer shall your name be called Abram,

But your name shall be Abraham;

For I have made you the father of a multitude of nations.6 I will make you exceedingly fruitful, and I will make nations of you, and kings will come forth from you. 7 I will establish My covenant between Me and you and your [f]descendants after you throughout their generations for an everlasting covenant, to be God to you and to your descendants after you. 8 I will give to you and to your descendants after you, the land of your sojournings, all the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession; and I will be their God.”

9 God said further to Abraham, “Now as for you, you shall keep My covenant, you and your descendants after you throughout their generations. 10 This is My covenant, which you shall keep, between Me and you and your descendants after you: every male among you shall be circumcised. 11 And you shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskin, and it shall be the sign of the covenant between Me and you.12 And every male among you who is eight days old shall be circumcised throughout your generations, a servant who is born in the house or who is bought with money from any foreigner, who is not of your descendants. 13 A servant who is born in your house or who is bought with your money shall surely be circumcised; thus shall My covenant be in your flesh for an everlasting covenant. 14 But an uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin, that person shall be cut off from his people; he has broken My covenant.”

15 Then God said to Abraham, “As for Sarai your wife, you shall not call her name Sarai, but Sarah shall be her name. 16 I will bless her, and indeed I will give you a son by her. Then I will bless her, and she shall be a mother of nations; kings of peoples will come from her.” 17 Then Abraham fell on his face and laughed, and said in his heart, “Will a child be born to a man one hundred years old? And will Sarah, who is ninety years old, bear a child?”

Looking at the beginning and ending of that passage, do you see items that repeat? Repeating words, phrases or ideas enable us to detect literary structures known as parallelisms, from which we will construct larger literary structures, chiasms.

We should immediately see “Abram fell facedown,” in line 3a vis-a-vis “Abraham fell facedown” in line 17a. This suggests the presence of a literary structure. Inside those verses, that is, after 3a and before 17a, are there other matching words, phrases and/or ideas?

What may next catch our attention is the “re-naming” of Abram to Abraham in verse 5 and Sarai to Sarah in verse 15b. There are two other similarities that follow this. Of Abraham, God states “I will make nations of you” in 6a paralleling “I will bless her (Sarah) so that she will be of nations.” (16b) Next, in 6b, we read of Abraham: “Kings will come from you.” Likewise, with Sarah, in 16b, we read: “Kings of peoples will come from her.”

We’re starting to connect the dots. Of Abraham and Sarah, nations will arise from them; kings will come from them. These declarations of God reveal His purpose for the couple. A genealogical path to David–and from there to Jesus–has been set into motion.

Returning to the literary structure, inside this matching set of parallelisms–Abraham falling facedown, the name changes, nations arising and kings coming forth–we find the key verses regarding circumcision. What in the world do any of these have to do with circumcision? It’s not immediately apparent, but the literary structure of the passage points to it.

Let’s focus on this aspect of naming. What is the significance of each change? The name, Abram, is a composite of two Hebrew words, ab meaning father, and rum meaning “to exalt.” So, taken together, we have “exalted father.” This word, rum, is used in the sense of lifting up, such as we find in Genesis 7:17–the “lifting up” of Noah’s Ark by flood waters, and in Genesis 14:22 in which Abram “lifts up” his hand to the LORD symbolic of swearing to an oath. The name, Abraham, includes ab meaning father, but combines it with an unused word–this has rendered the name of Abraham a bit mysterious. The latter half of verse 17:5 does say “I will make you a father of many nations.” The Hebrew for “father of many nations” is ab hamon goyim. This, we may surmise, connects to the meaning of the name, Abraham. And the name of Abraham is connected to the rise of nations and the coming forth of kings.

The names Sarai and Sarah derive from the same root, sar, meaning princess. Both names mean, essentially, the same thing. As with Abraham, the text associates the name of Sarah with the rise of nations and the coming forth of kings.

To see the importance to God of these name changes, and to connect them in some way with circumcision, we need to look back in Scripture to earlier points of time. Where do we find the first reference to naming?

We find the initial reference to naming in Genesis Chapter 2. Before going into that bit of detail, I believe it’s worthwhile to locate its context within the entire story of the creation of man. We may detect a pattern that will inform the naming discussion. This initial story begins in Genesis 2:7: “And the LORD God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living being.” God formed, that is, created man from the dust of the ground, that is, with the help of His creation. So, God was the primary actor here, the creation, secondary, that which was used by God to create a man. Is there a verse that parallels this? It turns out there is: Genesis 4:1, which I would consider the end of the story. “Now the man knew his wife, Eve, and she conceived and gave birth to Cain, and she said, ‘I have acquired a man with the LORD.'” In Hebrew, the word translated as “with” is et. When this word shows up in front of a noun, that noun becomes a direct object. Therefore, the LORD is the direct object and is One who Eve “used” to acquire Cain. Eve is the primary actor here, the subject, and the LORD is secondary, the object. In Genesis 2:7, God created a human being with the help of His creation, the earth. In Genesis 4:1, a human being created a human being with the help of God. In between, something has significantly shifted.

Between 2:7 and 4:1, another parallelism presents itself. In 2:25, we read: “The man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed.” The Hebrew for “ashamed” is boosh, meaning “aware.” The man and his wife were not “aware” of their nakedness; they had no self-awareness. Is there a verse that parallels this. Yes, verse 3:7a. “Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked.” The first humans became self-aware.[3] This occurred immediately after eating the forbidden fruit. For discussion purposes, we will call everything that transpired before eating the “pre-tree” world and everything after eating the “post-tree” world. A literary structure has emerged.

Inside both the “pre-tree” and the “post-tree” worlds, there are naming events. Do you see them? In Genesis 2:19, we read: “Out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field and every bird of the sky, and brought them to the man to see what he would call them; and whatever the man called a living creature, that was its name.” At this point, Adam had no “self-awareness.” He existed in the pre-tree world. He only had “God-awareness.” So, whatever he called each animal “that was its name.” Those names aligned with the purpose and will of God–they would be unchanging. Adam was not acting independently of God. What is the other naming event?

We find that in Genesis 3:20. “Now the man called his wife’s name, Eve, because she was the mother of all the living.” In Hebrew, Eve is called Chava. It is a derivative of the word, chay, meaning life. She is called “em kol chay,” mother of all life. Where is it that we find this verse? In the post-tree world. It follows immediately after God has told Adam “for you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Is this what you’d say or do after hearing those words from the Creator of the Universe? When God spoke to Adam, Adam spoke back, almost as if he was some sort of equal. When God spoke to Abraham, Abraham fell facedown. Two verses later, God stated: “Behold, the man has become like one of Us, knowing good and evil.” Verses 2:19 and 3:20 form an antithetical parallelism–in 2:19 a human being names the animals according to the purpose for which God created them–“and that was its name.” In 3:20, a human being names another human being, but there is no qualifier, nothing saying “and that was its name.” In addition, God authorized Adam to name the animals, bringing them to him “to see what he would name them.” In verse 3:20, Adam just names Eve without prior authorization–he acts independently. God started as the sole Creator of the living: and the LORD “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life.” (Gen. 2:7) That was pre-tree. Now, a human being is the “mother of all the living,” post-tree. (Gen. 3:20) The verse following 3:20 is also very telling: “The LORD God made garments of skin for Adam and his wife, and clothed them.” Is there a prior verse that parallels that? Yes–verse 3:7: “Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves loin coverings.” It happens that the making of loin coverings was the first and only act of “creating” done by human beings to this point in the narrative. And when Adam named Eve according to a purpose he assigned to her–“mother of all the living”–the very next thing God did was to create garments. If Adam and Eve purposed to be creators in their own right, to independently create something, and if the one and only thing they created was loin coverings, God was quick to assert His position as Creator of the universe, as the Creator of all, by producing His own coverings for the couple, by reasserting human dependence upon Him. This was not simply “gracious” as it is often sermonized; this was a reminder to the couple that God was the ultimate Creator, the sole independent Being in all existence. And just four verses later, the one whose name means “mother of all the living” looked at herself as the primary creator of a human being, an independent creator who used God for her purpose. A shift has occurred from God-centeredness to human centeredness. Wow.[4]

There is another incident, just before the time of Abraham, that embraces both the matter of names and the “shift” from God-centeredness to human-centeredness. Genesis Chapter 11 records the story of Babel. A question we might ask is why is this story found in this place of Scripture? Take note that just before that story, in Chapter 10, beginning in verse 21, we have the genealogy of Shem, the first son of Noah. Then comes the account of Babel. Immediately following that account is a second telling of the genealogy of Shem, beginning in verse 11:10. The latter genealogy leads all the way to Abram, something the version in chapter 10 does not do.

Shem, in Hebrew, means name. It consists of two Hebrew consonants, shin and mem. The first use of a word with only those two consonants is in Genesis 2:10: “Now a river flowed out of Eden to water the garden; and from there it divided and became four rivers.” Did you see it? The word spelled shin-mem, or shem, translates the English “there.” “From ‘there’ it divided.” Shem, that is, name, references the source of something. Looking back to Genesis 2:7, God was the “source” of life; in 3:20, Eve, being named by Adam, the “mother of all the living,” was deemed by him as the source of all life.

Is there something in the account of Babel mentioning the word, name? Yes, in verse 11:4: “They said, ‘Come, let us build for ourselves a city, and a tower (migdal from gadal meaning great) whose top (rosh) will reach into heaven, and let us make for ourselves (Heb.: la-nu) a name (shem).” They, the men of Babel, set as their purpose to build a “great” tower to make for themselves a “name.” This “name” they strived for was a “source” of self-identity. God frustrated these plans by confusing their language and scattering them across the face of the earth. The imagery here is that the great identity of man–this name–was dispersed over the earth, made small as if to vanish. The purpose of men was not in alignment with the purpose of God.

And what then did God do? After introducing the name of Abram within the second genealogy of Shem in Chapter 11, God converses with Abram in Chapter 12. The first genealogy of Shem represented a lineage operating according to man’s purpose and leading to Babel; the second was a lineage according to God’s purpose, leading to Abram, then to David, and ultimately to Christ. The first genealogy of Shem–and in Chapter 10, the other two sons of Noah–led to the mistaken idea that human beings could, of their own efforts, build a tower into heaven. The second genealogy of Shem leads to Abram, through whom God will redirect his self-centered creation back to Himself. And when God spoke to Abram, He told him: “And I will make you a great (gadal) nation, and I will bless you, and make your name (shem) great (gadal).” (12:2) It is not for man to purpose to build “great” towers to reach into heaven. Rather, it is for God to make “great” nations. It is not for men to make a name for themselves, to be the “source” of their own greatness–to make their own name great; rather it is God with whom the purpose of man is identified, and it is God with whom man is aligned. It is God, not man, who makes a name great.

How does this then find its way into understanding Genesis 17? When God renamed Abram and Sarai–humanly-given names–to Abraham and Sarah–names assigned by God Himself, it signaled His purpose to bring mankind back to Himself. Abraham and Sarah would become the “source” of nations and kings. A creation that dared to name its first woman, the mother of all the living, now would return its actual source of life, its Creator, the LORD. How do we know this? And does this, in some way, connect to circumcision?

There are two literary structures in Genesis 17 that point to this conclusion. Here is the first:

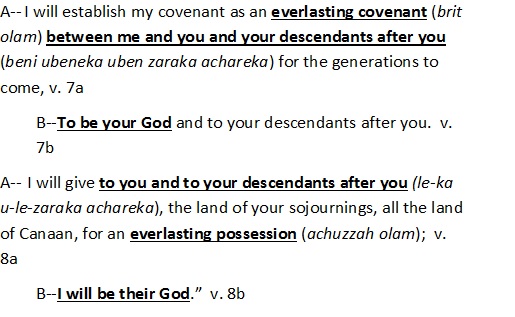

In line 7a, God proclaims a covenant between Himself and Abraham, including Abraham’s descendants: “I will establish my covenant as an everlasting covenant (brit olam) between me and you and your descendants after you (beni ubeneka uben zaraka achareka) for the generations to come.” This parallels a statement in line 8a, “I will give to you and to your descendants after you (le-ka u-le-zaraka achareka), the land of your sojournings, all the land of Canaan, for an everlasting possession (achuzzah olam);” This is a synthetic parallelism–line 7a offers a covenant in general terms, line 8a “amplifies” or “expands” on it by revealing the specifics. This reiterates the covenant regarding the inheritance of land promised to Abram in Chapters 12 and 15. In conjunction with this–and importantly just before the covenant of circumcision–are lines 7b and 8b, in which God asserts that He will be “your God and (God) to your descendants after you.” God is bringing His people to a land where He will redirect them to Himself. It is through Abraham and Sarah, freshly renamed, that God will purpose a “new beginning” for mankind.

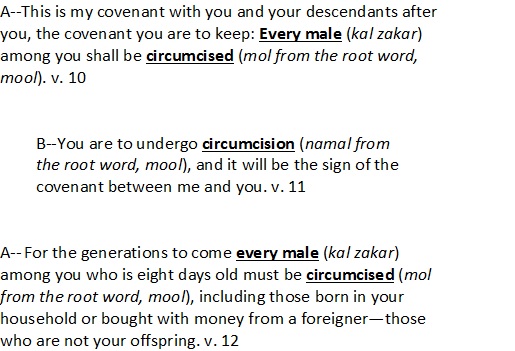

The second additional literary structure goes from verse 10 through verse 12. It centers specifically on circumcision, and like its previous counterpart, is located between the naming of Abraham and Sarah and God’s purpose for them.

Verses 10 and 12 are, like lines 7a and 8a, synthetic parallelisms. Verse 10 states that all males (kal zakar) will be circumcised. Verse 12 expands on that by stating that this will occur on the eighth day after birth[5], not only to Abraham’s offspring but also to those “who are not your offspring” but attached to the household. At the center of this chiasm, Abraham is specifically instructed to undergo circumcision “and it will be the sign of the covenant between me and you.” (v. 11)[6] The word in Hebrew for sign is oht, meaning a mark.[7] This same word is used in Genesis 4:15 in reference to Cain. It is also found in Genesis 9:12, 9:13 and 9:17, in reference to the rainbow that God would set in the sky as a “sign” of His covenant with Noah by which God promised never to destroy the earth by flood. So, if the rainbow is the sign of a covenant not to destroy the earth by flood, what is circumcision the sign for?

To discern a reason within Scripture, we begin with examining the word zakar. In our last literary structure, this word was translated as “male” in both verses 10 and 12. And those verses stand in parallel with each other, each authorizing/commanding the practice of circumcision. The Biblical author could have used the word, ish or adam, to refer to a man, or ben to refer to a son, but instead used zakar–male. The etymology or origin of this word traces back to the act of remembering, also zakar in Hebrew. This is true of a comparable word in Arabic, another language belonging to a larger circle of people known as Semites, descendants of Shem, the son of Noah, whose name, in turn, means name. The act of remembering, from the standpoint of its original meaning, is an act of pointing toward something that is not physically present.

Circumcision is intimately tied to the act of remembering. The mark of circumcision, every time it’s seen, points to something not physically present–alas, to Someone not physically present–to God. This is a means by which God “redirects” man to Himself. Although the sign of circumcision resides on the instrument of a man’s creativity, it serves as a reminder that even he who can create here on earth was himself created by Someone else, the LORD our God.

ENDNOTES

[1] As early as the second century B.C., Jewish sages differed on the necessity of circumcision during the conversion process. The Talmud records that R. Eliezer ben Hyrcanus required both circumcision and immersion in a mikveh; R. Joshua, on the other hand, only required immersion. 19th-century Reformers advocated to prohibit circumcision on the grounds that it was both unhealthy and barbaric, an unnecessary vestige of an ancient, outdated practice. (www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org)

[2] “The covenant of circumcision is of such great import that its observance takes precedence even over the Shabbat. This is perhaps due to the fact that by performing circumcision one actively accepts the very covenant one passively demonstrates by not doing the work activities (“melachot”) of Shabbat. Indeed, whereas one rests on Shabbat to identify with the Creator, so one performs brit milah to identify one’s active partnership with the Creator.” (Equal to All the Mitzvot in the Torah, Rabbi Mois Navon, Aish.com)

[3] This is further indicated by the question of God to Adam in v. 11: “Who told you that you were naked?” This would indicate that Adam would not have been previously aware of his nakedness unless God told him.

[4] In Genesis 2:2-3, it states that God rested from His work. The Hebrew used here for work is melachah. In Genesis 2:15, it states that God took Adam and put him in the garden to work and keep it. The word, work, in Genesis 2:15 is avodah. Melachah is used in Hebrew to describe “creative” work whereas avodah is simple laboring or tending. Man was, therefore, not placed on Earth to independently create, but rather to tend the work of his Creator. Jesus said: “For I have come down from heaven, not to do My own will, but the will of Him who sent Me.” (John 6:38)

[5] There is no explanation in Scripture for performing the circumcision on the 8th day. In Rabbinical literature, it was held that a Sabbath must pass before circumcision could occur. Therefore, if a baby boy was born on the Sabbath, it would be eight days before a full Sabbath had passed. It is reasoned that “the holiness of the Sabbath comes directly and exclusively from God. . .once the baby has experienced the ‘holiness’ of the Shabbos, he may enter into the covenant of the Jewish people.” (www.aish.com/ci/sam/48964686.html)

[6] Jewish tradition holds that “Adam was born without a foreskin. Only when he sinned did he create a barrier between himself and God and at that point developed a foreskin. The removal of t he foreskin represents the physical act by which man attempts to come close to God again.” (www.aish.com/ci/sam/48964686.html)

[7] R. Hirsch (Ber. 17:10, p.301) explains that the sign (“oht”) of circumcision symbolizes complete submission to the authority of God, such total compliance being indicative of serving God in awe (“yareh”). Hence, the relationship occurs between this response and Abraham falling facedown.